Change of variables (PDE)

Often a partial differential equation can be reduced to a simpler form with a known solution by a suitable change of variables.

The article discusses change of variable for PDEs below in two ways:

- by example;

- by giving the theory of the method.

Contents |

Explanation by example

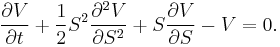

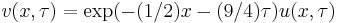

For example the following simplified form of the Black–Scholes PDE

is reducible to the heat equation

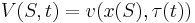

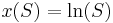

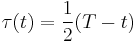

by the change of variables[1]:

in these steps:

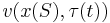

- Replace

by

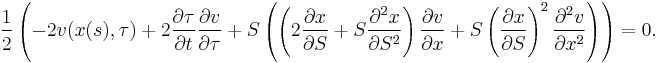

by  and apply the chain rule to get

and apply the chain rule to get

- Replace

and

and  by

by  and

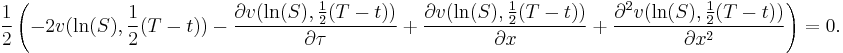

and  to get

to get

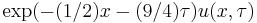

- Replace

and

and  by

by  and

and  and divide both sides by

and divide both sides by  to get

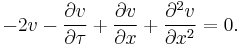

to get

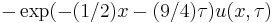

- Replace

by

by  and divide through by

and divide through by  to yield the heat equation.

to yield the heat equation.

Advice on the application of change of variable to PDEs is given by mathematician J. Michael Steele[2]:

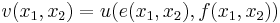

"There is nothing particularly difficult about changing variables and transforming one equation to another, but there is an element of tedium and complexity that slows us down. There is no universal remedy for this molasses effect, but the calculations do seem to go more quickly if one follows a well-defined plan. If we know that

satisfies an equation (like the Black–Scholes equation) we are guaranteed that we can make good use of the equation in the derivation of the equation for a new function

defined in terms of the old if we write the old V as a function of the new v and write the new

and x as functions of the old t and S. This order of things puts everything in the direct line of fire of the chain rule; the partial derivatives

,

and

are easy to compute and at the end, the original equation stands ready for immediate use."

Technique in general

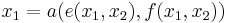

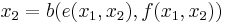

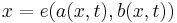

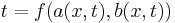

Suppose that we have a function  and a change of variables

and a change of variables  such that there exist functions

such that there exist functions  such that

such that

and functions  such that

such that

and furthermore such that

and

In other words, it is helpful for there to be a bijection between the old set of variables and the new one, or else one has to

- Restrict the domain of applicability of the correspondence to a subject of the real plane which is sufficient for a solution of the practical problem at hand (where again it needs to be a bijection), and

- Enumerate the (zero or more finite list) of exceptions (poles) where the otherwise-bijection fails (and say why these exceptions don't restrict the applicability of the solution of the reduced equation to the original equation)

If a bijection does not exist then the solution to the reduced-form equation will not in general be a solution of the original equation.

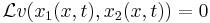

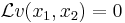

We are discussing change of variable for PDEs. A PDE can be expressed as a differential operator applied to a function. Suppose  is a differential operator such that

is a differential operator such that

Then it is also the case that

where

and we operate as follows to go from  to

to

- Apply the chain rule to

and expand out giving equation

and expand out giving equation  .

. - Substitute

for

for  and

and  for

for  in

in  and expand out giving equation

and expand out giving equation  .

. - Replace occurrences of

by

by  and

and  by

by  to yield

to yield  , which will be free of

, which will be free of  and

and  .

.

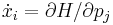

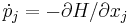

Action-angle coordinates

Often, theory can establish the existence of a change of variables, although the formula itself cannot be explicitly stated. For a integrable Hamiltonian system of dimension  , with

, with  and

and  , there exist

, there exist  integrals

integrals  . There exists a change of variables from the coordinates

. There exists a change of variables from the coordinates  to a set of variables

to a set of variables  , in which the equations of motion become

, in which the equations of motion become  ,

,  , where the functions

, where the functions  are unknown, but depend only on

are unknown, but depend only on  . The variables

. The variables  are the action coordinates, the variables

are the action coordinates, the variables  are the angle coordinates. The motion of the system can thus be visualized as rotation on torii. As a particular example, consider the simple harmonic oscillator, with

are the angle coordinates. The motion of the system can thus be visualized as rotation on torii. As a particular example, consider the simple harmonic oscillator, with  and

and  , with Hamiltonian

, with Hamiltonian  . This system can be rewritten as

. This system can be rewritten as  ,

,  , where

, where  and

and  are the canonical polar coordinates:

are the canonical polar coordinates:  and

and  . See V. I. Arnold, `Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics', for more details.[3]

. See V. I. Arnold, `Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics', for more details.[3]

References

- ^ Solution of the Black Scholes Equation

- ^ J. Michael Steele, Stochastic Calculus and Financial Applications, Springer, New York, 2001

- ^ V. I. Arnold, Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, v. 60, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1989